Behind Falungong and Li Hongzhi

Canada’s recently crowned Miss World contestant Anastasia Lin testified before the US Congress last week on the supposed “plight” of followers of the Falungong cult in China. She also stars as an imprisoned practitioner in an upcoming Canadian movie about the sect.

In the West, the group is often portrayed as innocently practicing qigong breathing exercises and a pseudo-religion based on a mish-mash of Buddhism, Taoism, other religions, and its leader Li Hongzhi’s convoluted, self-conflicting and fantastical teachings. But, its sordid past betrays an ostensibly benign exterior. And despite their denials and propaganda spewed by its mouth-piece the Epoch Times, their activities in and outside China then as now are highly political.

The following are excerpts from now defunct Asiaweek magazine reports about the cult after it initially popped into the international limelight in 1999. (The excerpts have been adapted to account for the time change.):

In April 1999, 10,000 Falungong devotees surrounded Beijing’s Zhongnanhai leadership compound, prompting the authorities to crackdown against the cult a couple months later. At the time, Falungong claimed 60 million followers in China and 40 million abroad but experts estimate that at its height membership amounted to no more than 2 million in China.

What is Falungong? The term actually applies to the five exercises practiced as part of Falun Dafa, or the Buddha Law (Dafa) of the Wheel of Law (Falun), but has come to mean the sect. At its simplest, Falungong combines qigong, traditional breathing exercises that channel the body’s qi (energy), with a moral philosophy centered on zhen (truthfulness), shan (benevolence), and ren (forbearance). It sounds benign enough. The details are a bit more esoteric.

In the sect’s bible, Zhuan Falun (Rotating the Falun), Li Hongzhi uses anecdotes from Buddhism, Taoism, science and daily life to explain that a Falun is rotating endlessly in the universe. By practicing Falungong and studying its texts, a devotee can get a small wheel in his or her abdomen, which spins one way to absorb energy, and the other way to eliminate harmful elements. With continued study and practice, adherents can ascend to higher levels, acquire a “third eye” (that peeps through an opening in the cranium) to commune with the universe, and eventually achieve “perfect happiness.”

That only scratches the surface of what adherents experience. Ms. Wang, 32, a laid-off oil industry worker in northeastern China, describes what happens when she practices Falungong: “I feel the qi going along channels in my body. Sometimes I feel an intense pulse. I can see lights, but only faintly [because] I haven’t deepened my practice yet. After practice, I feel peaceful.”

Devotees claim that pain and disease diminish or disappear after just weeks of practice. “So many sufferers of deadly ailments who were given the death sentence by modern medicine made miraculous recoveries,” wrote Wang Youqun, then a senior legal cadre, in an open letter to party leaders. “Who could have purified so many practitioners in such a short time to eliminate disease? No one but Li Hongzhi.”

In a sense, Falungong is one of a long line of qigong practices that offer disciples health and strength. (Li in Zhuan Falun denies that Falungong cures diseases, but the group’s website at the time boasted a “disease healing rate” of 99.1%.) The ancient tradition has enjoyed renewed popularity since the 1980s. What sets Falungong apart is that Li Hongzhi simplified the arduous and often secret qigong exercises, married them to a moral, if esoteric, philosophy, and set himself up as a teacher equal to Buddha.

Practitioners must study Li’s books and watch his videos continuously if they want to advance. Such requirements enrapture some Falungong devotees. Says Sterling Campbell, a New York-based musician: “Trying to be a good person in accordance with Falun Dafa is incredibly hard but I can’t imaging living any other way now. I can honestly say I’m happier, on a much deeper level.” From such beliefs spring devotion.

But, behind the seemingly innocuous spiritual teachings lies a dark side. Take the example of Zhang Yuqin, a middle-aged garment worker in Nanjing when she took up Falungong in 1995, practicing and studying Li Hongzhi’s books and videos incessantly. By 1997, she was claiming that Falungong cured all ills. She also began worrying about the end of the world. Later, she told her husband that she was a reincarnated male truck driver. Finally, in January 1998, her husband found her dead, her wrists slit.

Or how about Jiang Wenli, a retired paper-plant worker in Anhui province. In December 1999, she became delirious, killed her husband with an axe and scissors, cut some flesh from his buttocks and ate it. Later, she was heard shouting: “Li Hongzhi, come and save me!” Her son found her dead the next day. All told, authorities claim that over 1,400 deaths can be directly attributed to suicides and deranged killings by frenzied Falungong practitioners.

Adherents say the authorities are playing fast and loose with cause and effect. “Those with mental illness also go into delirium while practicing other forms of qigong,” says one follower. “Master Li forbids those with mental illness to practice Falungong. If they do anyway, they take the risk.” Besides, simply adding up all the devotee deaths does not mean much by itself, he argues. “In Beijing hospitals, 300 people die each day. In a year, how many would that make?” he snorts. “The government is using the deaths to scare people.”

To be fair, despite a couple self-emulations on Tiananmen Square that resulted in death and horrendous facial and body burns in protest of the cult’s banning, Falungong has not embarked on collective suicides (like the Switzerland-based Order of the Solar Temple whose members killed themselves between 1994 and 1999), or mass murder (like the nerve gas attack by Japan’s Aum Shinrikyo in 1995) or sexual abuse or even old-fashioned financial exploitation.

What Falungong does do is besiege opponents, literally. Li Hongzhi’s demand that followers “promote the law” and “protect the law” seems to foster intolerance of criticism. Believers encircled media organizations in China 77 times in the late 1990s (and once in Hong Kong) over what they said was unfair coverage. When they encircled Zhongnanhai in April 1999 to demand the leadership look into their grievances, it was the largest demonstration of any kind since the 1989 Tiananmen protests. Moreover, it took the authorities completely by surprise, although thousands had come from across the country.

Li further teaches that action to promote and protect the sect can help devotees reach higher levels. Despite Li’s repeated avowals that Falungong has no political interests, the way his sect rallied so many in as political an act as besieging Zhongnanhai, without tipping off security organs, at a time of rising discontent, must have shaken the authorities.

It is not just the powers-that-be who are concerned. Tang Lap-kwong, a lecturer in Chinese philosophy at the City University of Hong Kong, worries about the herd mentality he sees in devotees. (The sect is legal in Hong Kong.) “Members don’t have their individuality any more. They speak and behave like one person,” Tang says. “They only need slight guidance and then they will do anything en masse.” People who feel weak or lost seem particularly ripe for Falungong’s message.

Chan Kinman, professor of sociology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, says Falungong fills a “market niche” in an environment where, on the one hand, people were worried about access to health care following market reforms and, on the other, traditional morality had been devastated first by the Cultural Revolution and then by the dismantling of Maoist dogma and the plunge into economic liberalization.

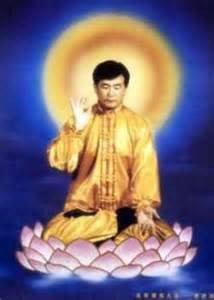

Falungong Leader Li Hongzhi, A Self-Proclaimed ‘Living Buddha’

“About 1.78 meters in height, with slanted eyebrows, single-edged eyelids, a little bit fat.” That was how China’s Ministry of Public Security described Li Hongzhi, 47 (now 63?). In an all-points bulletin issued nationwide on July 29, 1999, police and border troops across the country were ordered to “make arrangements to track down Li’s whereabouts and arrest him.” The command, however, just wasn’t practical. Li is a resident of New York City and China has no extradition treaty with the United States.

A one-time food grains clerk from Jilin province, he began learning his art under qigong masters in 1988. Li formed the Falungong movement in 1992 and moved to the U.S. four years later. The sect’s essential principles are contained in the “Wheel of the Law Breathing Exercise,” Falungong’s circle-shaped emblem, derived from a Buddhist symbol for the universe and its powers.

So why were the security services after Li? On April 25, 1999, Li had slipped into the country to organize a rally against the government. Some 10,000 adherents of Falungong staged a day-long silent protest outside the Zhongnanhai compound where Beijing’s leaders live. Early that morning, former Premier Zhu Rongji strode out of his residence to meet Falungong representatives, looking highly irritated. He had returned from an official trip to the U.S. the previous night and had hardly slept. The Falungong demanded the release of five followers during an earlier demonstration in the city of Tianjin and the dismissal of the editor of a local youth magazine that had rebuked the sect’s beliefs.

Negotiations continued late into the evening and Falungong leaders departed with promises of a resolution. Within two hours, most protesters were bussed to the distant Beijing West railway station and given tickets home. On July 22, 1999, Beijing outlawed the sect, accusing it of “spreading fallacies, hoodwinking people, inciting and creating disturbances and jeopardizing social stability.” Officials branded Li a charlatan, banned his group’s publications and launched a sweeping crackdown against its members. Then U.S. President Bill Clinton described the offensive as a “troubling example” of the government’s action against those “who test the limits of freedom.”

Performing qigong is supposed to make the wheel turn, enabling practitioners to tap in to the energy pervading the universe. Further, Falungong is unique among qigong disciplines because it is portrayed as a holistic way of living rather than just an aid to good health. Li’s book, Zhuan Falun (“Turning the Dharma Wheel”), the sect’s bible, deals with such moral philosophical concepts as zhen (truth), shan (goodness) and ren (forbearance).

His disciples see him as a “living Buddha.” He also has an astonishing capacity to spread his message. The Falungong has been known to mobilize followers through the Internet and is adept at using videos and publishing material as propaganda tools. Prior to the crackdown on the sect, Li’s books could be found in most bookstores across China, even in state-run outlets such as Xinhua. His works are distributed worldwide in seven languages and taught in China by “cultivation groups” in nine-day classes free of charge. Before the purge, there were as many as 28,000 such groups in the mainland.

Falungong’s membership are often retired people and other marginalized folk who turn to Li’s teachings to fill a spiritual void in their lives. Quite a few are party members. Despite such a following, Li describes himself as “just a very ordinary man.” But that’s clearly not what he set out to be. According to an official probe, Li changed his date of birth from July 7 to May 13, which happens to be the day on which the Buddha was born.