China Ratifies Paris Climate Change Accord

Today, China announced it has ratified the emissions-cutting agreement reached last year in Paris, giving a big boost to efforts to bring the accord into effect by the end of this year. The United States was also expected to announce that it was formally joining the Paris Agreement in advance of the Group of 20 summit.

China is the top emitter of man-made carbon dioxide emissions, and the United States is second. Together, they produce 38 percent of the world’s man-made carbon dioxide emissions.

Both were key to getting an agreement in Paris last year. To build momentum for a deal, they set a 2030 deadline for emissions to stop rising and announced their “shared conviction that climate change is one of the greatest threats facing humanity.”

-AP

Investment Cuts Both Ways

China has been on a worldwide buying binge in recent years with its state-owned enterprises (SOEs) splurging US$111.6 billion (C$146 billion) in the first seven months of this year alone, reported Reuters. That figure already surpasses the US$111.5 billion mark set by China’s outbound FDI for the entire year last year and approaches the total amount of inbound FDI of US$126.27 billion. But, as Chinese state firms celebrate their successes, they face increasing push-back on national security and market access grounds, not to mention totally unrelated red herrings such as China’s South China Sea (SCS) claims and ‘human rights’ record.

Two cases in particular stand out – in July, the post-Brexit-Cameron government of Theresa May launched a surprise review of the US$24 billion Hinkley Point nuclear project at Somerset which is being co-financed by SOE China General Nuclear Power Corp. (CGNPC), bringing a sharp halt to the much-touted “golden age” of China-UK relations spearheaded by the former Cameron-Osborne team.

Then, in August, Australia blocked the A$10 billion (C$9.887 billion) sale of a 50.4% stake in Ausgrid to China’s State Grid Corp. and Li Ka-Shing’s Cheung Kong Infrastructure Holdings. Analysts believe the veto, which follows the ban on the massive 101,000 km2 Kidman family farm sale to Chinese interests last year, owes much to seats won by the NXT and the One Nation party, two right-wing protectionist blocs in the Australian Senate following recent national elections.

The decisions did not go down well in Beijing. In the wake of May’s decision, Chinese Ambassador to the UK Liu Xiaoming warned, “the China-UK relationship is at a crucial historical juncture. Mutual trust should be treasured even more.” The situation has not been helped by the fact that a trusted advisor of the new Prime Minister who has her close ear is an ardent Sinophobe who wrote a scathing diatribe against China last October accusing the previous government of selling out Britain’s national security. On top of that, the US Justice Department charged an American national working for CGNPC of illegally developing and producing special nuclear material in China.

In a bid to appease the Chinese, Ms May sent a high-ranking Foreign Office official to reassure Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi that Britain attached utmost importance to Sino-British cooperation. Ms May also made a personal appeal to Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang in the form a letter. Currently on her first trip to Beijing as Prime Minister for the G20 Summit, she’s seeking to comfort the Chinese that despite the Hinkley delay, Britain wants to solidify ties that are wide-ranging and multi-faceted.

In blocking the Ausgrid deal, the Australian authorities had expressed concerns that the main electricity network serving 1.6 million homes and businesses in Sydney and beyond in New South Wales, the country’s largest state with 7.5 million inhabitants, could be compromised in times of crisis. Although Scott Morrison, Australia’s Treasurer, declined to comment on specific national security risks the sale posed, sources cited dangers of Chinese cyberattacks and electronic espionage. Not surprisingly, xenophobic Senators in the governing coalition pointed to SOEs, the SCS dispute, and the nature of the Chinese government as key red flags.

But, red herrings aside, there is nonetheless a palpable change in foreign attitudes toward Chinese investment in general and Chinese SOE money in particular. “Protectionism is resurfacing. In many parts of the world, we have seen calls for deglobalization”, commented Chinese deputy Foreign Minister Li Baodong. But, it’s not just trade protectionism that’s rearing its ugly head but Western business groups and government officials are ever louder raising long-standing gripes about access of their companies to the Chinese market.

They point to restrictions on foreign companies in Chinese industries such as financial services, healthcare, and logistics. Just prior to the G20 Summit, a European Union Chamber of Commerce (EUCC) annual paper stated bluntly, “this unbalanced situation is not political sustainable and for its own benefit, China should begin reciprocating by opening and allowing European business to contribute more to its economy…If it is ultimately unwilling to offer reciprocal access to its own market, China cannot assume that it will indefinitely continue to enjoy open and unhindered access to the EU’s.”

Joerg Wuttke, President of the EUCC in China warned of a protectionist backlash saying nowadays European officials are more daring to speak their minds on the reciprocity issue. “It has reached the point where people are not afraid to speak up anymore. They feel like they have to be tougher in front of their constituencies”, Mr Wuttke told the media. A EU official involved in China trade added, “The Chinese would shut you down at once if you said you wanted to buy one of their grids. You wouldn’t get to the end of the sentence”.

In terms of policy, the EU recently introduced a groundbreaking expanded review process focusing on all assets managed by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) under China’s State Council. This means an extra layer of oversight that could delay or even scuttle future Chinese SOE M & As of European companies, forcing them to jump through more hoops in a lengthy approval process.

The good news is that, on the other side of the Atlantic, the latest annual China-US Strategic and Economic Dialogue ended with a commitment to expedite the conclusion of a Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT), a key issue for which is foreign access to protected sectors and the whittling down of China’s “negative list” of off-limits industries.

The US-China Business Council (USCBC) declared: “a high-quality US-China BIT would give American companies better access to China’s market and equal rights as Chinese firms”. A BIT would also help alleviate Chinese concerns over the activities of the US government agencies such as the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States which has blocked a number of Chinese investments in the US before.

Robert Held, a Geneva-based financial consultant writing in the Asia Times newspaper suggests unless China starts allowing more reciprocity in market access, mistrust over China’s SOEs will only rise. Protectionism against Chinese SOEs “will become more stringent (in the US) and even more dramatically, in the EU, could become the norm. The writing is on the wall: reciprocity can no longer be postponed by Beijing without hurting its own interests”, he argued.

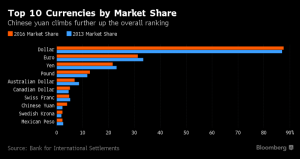

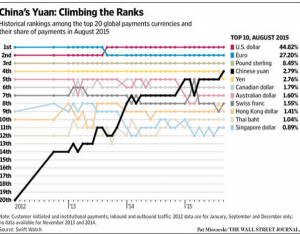

RMB’s Share of Global Trading Doubles in Three Years: BIS

Currency analysts and RMB trackers are predicting the RMB will take fourth spot by 2020.

______________________

China’s yuan has doubled its share of global currency trading in the three years through April 2016, according to the latest triennial survey conducted by the Bank for International Settlements.

The yuan’s average daily turnover rose to $202 billion in April from $120 billion in the same month of 2013, boosting its ratio of global foreign-exchange trading to 4 percent from the previous 2 percent, the survey results show. That puts the currency in eighth place overall. Dollar-yuan became the sixth-most traded currency pair, advancing from ninth place in 2013, BIS said, while the yuan overtook the Mexican peso as the most actively traded emerging-market currency.

The survey polled central banks and other authorities in 52 jurisdictions, with data from almost 1,300 banks and other dealers, BIS said. The dollar increased its lead as the most-traded currency with 88 percent of deals, up a percentage point from three years ago. The euro remained No. 2, though its share fell to 31 percent. Yuan transactions in both the onshore and overseas markets were –

The Bank for International Settlements report comes a month before the yuan is scheduled to join the dollar, euro, British pound and Japanese yen in the International Monetary Fund’s basket of global reserves.

– Bloomberg on finance.yahoo.com

Seeking a “New Opportunity” or Back to “Canadian Mode”

Justin Trudeau is making a state visit to China followed by a grand appearance at the G20 Summit in Hangzhou. In the lead-up to the week-long visit, there has been much ado about Canada’s relations with the Asian superpower – deepening ties with and latching onto China’s economic coattails pitted against Canadian uninformed and in many instances misplaced anxiety over China’s “human rights” record. However, the Trudeau government, like its predecessor, may not be able avoid succumbing to divided Canadian public opinion and revert to a go-slow pace in Canada’s relations with China.

Take murmurings about Canada-China free trade agreement (FTA) talks. Despite some gung-ho hot air late last year after the election about looking at it closely, the Trudeau government has since decided to back off, intimating that it might not happen for years to come!! While Trudeau et al. may want to avoid the roller coaster ride of the Harper government, it is sending mixed messages to the Chinese who believe there is a “new opportunity” to strengthen ties and “reset” the relationship.

Meanwhile, as Canada twiddles its thumbs over FTA talks, the Kiwis and the Aussies are already miles ahead. Signed and brought into force in 2008, the China-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement is the first FTA between China and a developed country that has brought New Zealand immense profit. To be phased in gradually over 12 years with full implementation in 2019, the FTA has already served to increase especially agricultural exports from NZD2.2 billion (US$1.8 billion) in the first year to NZD8.6 billion, a nearly four-fold increase, four years later. The primary beneficiaries of the FTA are New Zealand’s dairy industry (NZD2.8 billion), wood products (NZD1.2 billion), and meat industries (NZD412 million). In the process, China overtook Australia as New Zealand’s largest export market.

The FTA was deemed so crucial to the New Zealand economy that its Prime Minister sought an upgrade that is expected to be completed by this year end. Not to be outdone, but nonetheless 7 years behind New Zealand, the Aussies signed their own FTA with China in June last year which came into force at year end. Upon full implementation of the agreement, 95% of Australian exports to China will become tariff free including many agricultural products notably beef and dairy. In addition, Australia’s services sector will be more open to private Chinese investment with projects under AD1.078 billion not requiring Foreign Investment Review Board approval.

So, there lies the dilemma for Canada – getting cold feet over fleeting public opinion and returning to slow motion on the importance of a FTA with China and sit on the sidelines as the Kiwis and Aussies reap the benefits of free trade at the expense of Canada. After all, they are direct competitors for many of the products Canada wishes to sell to China such as lumber, seafood, BC fruit and so on.

Yet, all is not lost. If a free trade deal is not in the cards, there is still ample that Canada can do short of one; that is, if Trudeau’s government truly listens to the valuable advice offered by Dominic Barton, managing director of McKinsey & Co. and the chair of the government’s economic growth advisory board. Mr Barton urges the government to move quickly on various fronts including financial and health-care services, the agri-food trade, coaxing more Chinese students to study in Canada, and finding ways for Canadian small and medium-sized companies (SMEs) to tap into China’s vast consumer markets through e-commerce companies like Alibaba and JD.com. Australia, for example, earns $20 billion a year from educating foreigners in its schools, a big segment of who are Chinese students.

Mr Barton’s company projects within a short span of 6 years (by 2022), China’s middle class (not simply the current 730 million urbanites that include working classes and migrants) will balloon to over 550 million. Among them, owing to higher-paying high-tech and services jobs, 54% will have become “upper middle” class that earn between US$16,0000 to $34,000 a year. Meanwhile, a study by consulting competitor Boston Consulting Group expects Chinese consumption to grow by 9% a year through 2020. Overall, the consumer economy is forecast to grow by 55% to US$6.5 trillion, increasing $2.3 billion or the current consumption sum of Germany or the UK. And that projection is based on the very conservative assumption that China’s economy grows by 5.5% a year, much lower than the current 6.5% to 6.7%.

Mr Barton also called on the government to reverse the former Harper government’s shut-down of Chinese investment by making capital investments more politically palatable to the Canadian public than wholesale takeovers of Canadian companies by China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs). He also sees many aspects of the China trade-investment equation as interconnected – growing food demand from China’s burgeoning middle class over the next few years could lead to the expansion of Canada’s rail network for which China could readily invest in/build related equipment such as rail cars, locomotives, and systems. That, in turn, could tweak Chinese interest to take part in building high-speed rail (HSR) corridors in eastern Canada and elsewhere.

Finally, advisor Barton also wants to promote Canadian research and development through collaboration with Chinese venture capital and other investment as well as Chinese tech firms to establish tech clusters in clean energy for example. As for Canadian concerns about “human rights”, Mr Barton argued compellingly Canada would be better served and wield more influence through the boosting of economic and investment ties. “I think it’s very difficult to admonish people with no relationship because it’s kind of like, ‘Why should I listen to you?’, he reflected. In the void of deepening economic and cultural engagement, Canadian self-righteous utterances only sound hollow and hypocritical and do little to help change mindsets.

From the activities of Canadian ministers over the recent past, there may yet be some hope for more enlightened policy. Finance Minister Bill Morneau indicated Canada may consider relaxing its foreign investment rules, including a more accommodating approach to China’s SOE investment. Asked about reviewing restrictions on SOE acquisitions of Canadian oil assets, Morneau said his government expects to discuss with the Chinese how to spur more investment in Canada.

In a related development, Minister of Immigration John McCallum discussed with Chinese Foreign Affairs and Public Security officials in early August on opening five more visa offices in Chinese second-tier cities Chengdu, Nanjing, Wuhan, Jinan, and Shenyang, to bring the number to 15. This is to smooth the path for more Chinese to study in Canada; place more foreign talent in high-tech jobs; bring in more Chinese investment; as well as more tourists who spend more than other cohorts while in Canada. The government is even studying ways to revamp the investor immigrant program which was cancelled by the Conservatives after it amassed a backlog of about 65,000 applicants, mostly from China, followed by a failed replacement program.

Behind Falungong and Li Hongzhi

Canada’s recently crowned Miss World contestant Anastasia Lin testified before the US Congress last week on the supposed “plight” of followers of the Falungong cult in China. She also stars as an imprisoned practitioner in an upcoming Canadian movie about the sect.

In the West, the group is often portrayed as innocently practicing qigong breathing exercises and a pseudo-religion based on a mish-mash of Buddhism, Taoism, other religions, and its leader Li Hongzhi’s convoluted, self-conflicting and fantastical teachings. But, its sordid past betrays an ostensibly benign exterior. And despite their denials and propaganda spewed by its mouth-piece the Epoch Times, their activities in and outside China then as now are highly political.

The following are excerpts from now defunct Asiaweek magazine reports about the cult after it initially popped into the international limelight in 1999. (The excerpts have been adapted to account for the time change.):

In April 1999, 10,000 Falungong devotees surrounded Beijing’s Zhongnanhai leadership compound, prompting the authorities to crackdown against the cult a couple months later. At the time, Falungong claimed 60 million followers in China and 40 million abroad but experts estimate that at its height membership amounted to no more than 2 million in China.

What is Falungong? The term actually applies to the five exercises practiced as part of Falun Dafa, or the Buddha Law (Dafa) of the Wheel of Law (Falun), but has come to mean the sect. At its simplest, Falungong combines qigong, traditional breathing exercises that channel the body’s qi (energy), with a moral philosophy centered on zhen (truthfulness), shan (benevolence), and ren (forbearance). It sounds benign enough. The details are a bit more esoteric.

In the sect’s bible, Zhuan Falun (Rotating the Falun), Li Hongzhi uses anecdotes from Buddhism, Taoism, science and daily life to explain that a Falun is rotating endlessly in the universe. By practicing Falungong and studying its texts, a devotee can get a small wheel in his or her abdomen, which spins one way to absorb energy, and the other way to eliminate harmful elements. With continued study and practice, adherents can ascend to higher levels, acquire a “third eye” (that peeps through an opening in the cranium) to commune with the universe, and eventually achieve “perfect happiness.”

That only scratches the surface of what adherents experience. Ms. Wang, 32, a laid-off oil industry worker in northeastern China, describes what happens when she practices Falungong: “I feel the qi going along channels in my body. Sometimes I feel an intense pulse. I can see lights, but only faintly [because] I haven’t deepened my practice yet. After practice, I feel peaceful.”

Devotees claim that pain and disease diminish or disappear after just weeks of practice. “So many sufferers of deadly ailments who were given the death sentence by modern medicine made miraculous recoveries,” wrote Wang Youqun, then a senior legal cadre, in an open letter to party leaders. “Who could have purified so many practitioners in such a short time to eliminate disease? No one but Li Hongzhi.”

In a sense, Falungong is one of a long line of qigong practices that offer disciples health and strength. (Li in Zhuan Falun denies that Falungong cures diseases, but the group’s website at the time boasted a “disease healing rate” of 99.1%.) The ancient tradition has enjoyed renewed popularity since the 1980s. What sets Falungong apart is that Li Hongzhi simplified the arduous and often secret qigong exercises, married them to a moral, if esoteric, philosophy, and set himself up as a teacher equal to Buddha.

Practitioners must study Li’s books and watch his videos continuously if they want to advance. Such requirements enrapture some Falungong devotees. Says Sterling Campbell, a New York-based musician: “Trying to be a good person in accordance with Falun Dafa is incredibly hard but I can’t imaging living any other way now. I can honestly say I’m happier, on a much deeper level.” From such beliefs spring devotion.

But, behind the seemingly innocuous spiritual teachings lies a dark side. Take the example of Zhang Yuqin, a middle-aged garment worker in Nanjing when she took up Falungong in 1995, practicing and studying Li Hongzhi’s books and videos incessantly. By 1997, she was claiming that Falungong cured all ills. She also began worrying about the end of the world. Later, she told her husband that she was a reincarnated male truck driver. Finally, in January 1998, her husband found her dead, her wrists slit.

Or how about Jiang Wenli, a retired paper-plant worker in Anhui province. In December 1999, she became delirious, killed her husband with an axe and scissors, cut some flesh from his buttocks and ate it. Later, she was heard shouting: “Li Hongzhi, come and save me!” Her son found her dead the next day. All told, authorities claim that over 1,400 deaths can be directly attributed to suicides and deranged killings by frenzied Falungong practitioners.

Adherents say the authorities are playing fast and loose with cause and effect. “Those with mental illness also go into delirium while practicing other forms of qigong,” says one follower. “Master Li forbids those with mental illness to practice Falungong. If they do anyway, they take the risk.” Besides, simply adding up all the devotee deaths does not mean much by itself, he argues. “In Beijing hospitals, 300 people die each day. In a year, how many would that make?” he snorts. “The government is using the deaths to scare people.”

To be fair, despite a couple self-emulations on Tiananmen Square that resulted in death and horrendous facial and body burns in protest of the cult’s banning, Falungong has not embarked on collective suicides (like the Switzerland-based Order of the Solar Temple whose members killed themselves between 1994 and 1999), or mass murder (like the nerve gas attack by Japan’s Aum Shinrikyo in 1995) or sexual abuse or even old-fashioned financial exploitation.

What Falungong does do is besiege opponents, literally. Li Hongzhi’s demand that followers “promote the law” and “protect the law” seems to foster intolerance of criticism. Believers encircled media organizations in China 77 times in the late 1990s (and once in Hong Kong) over what they said was unfair coverage. When they encircled Zhongnanhai in April 1999 to demand the leadership look into their grievances, it was the largest demonstration of any kind since the 1989 Tiananmen protests. Moreover, it took the authorities completely by surprise, although thousands had come from across the country.

Li further teaches that action to promote and protect the sect can help devotees reach higher levels. Despite Li’s repeated avowals that Falungong has no political interests, the way his sect rallied so many in as political an act as besieging Zhongnanhai, without tipping off security organs, at a time of rising discontent, must have shaken the authorities.

It is not just the powers-that-be who are concerned. Tang Lap-kwong, a lecturer in Chinese philosophy at the City University of Hong Kong, worries about the herd mentality he sees in devotees. (The sect is legal in Hong Kong.) “Members don’t have their individuality any more. They speak and behave like one person,” Tang says. “They only need slight guidance and then they will do anything en masse.” People who feel weak or lost seem particularly ripe for Falungong’s message.

Chan Kinman, professor of sociology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, says Falungong fills a “market niche” in an environment where, on the one hand, people were worried about access to health care following market reforms and, on the other, traditional morality had been devastated first by the Cultural Revolution and then by the dismantling of Maoist dogma and the plunge into economic liberalization.

Falungong Leader Li Hongzhi, A Self-Proclaimed ‘Living Buddha’

“About 1.78 meters in height, with slanted eyebrows, single-edged eyelids, a little bit fat.” That was how China’s Ministry of Public Security described Li Hongzhi, 47 (now 63?). In an all-points bulletin issued nationwide on July 29, 1999, police and border troops across the country were ordered to “make arrangements to track down Li’s whereabouts and arrest him.” The command, however, just wasn’t practical. Li is a resident of New York City and China has no extradition treaty with the United States.

A one-time food grains clerk from Jilin province, he began learning his art under qigong masters in 1988. Li formed the Falungong movement in 1992 and moved to the U.S. four years later. The sect’s essential principles are contained in the “Wheel of the Law Breathing Exercise,” Falungong’s circle-shaped emblem, derived from a Buddhist symbol for the universe and its powers.

So why were the security services after Li? On April 25, 1999, Li had slipped into the country to organize a rally against the government. Some 10,000 adherents of Falungong staged a day-long silent protest outside the Zhongnanhai compound where Beijing’s leaders live. Early that morning, former Premier Zhu Rongji strode out of his residence to meet Falungong representatives, looking highly irritated. He had returned from an official trip to the U.S. the previous night and had hardly slept. The Falungong demanded the release of five followers during an earlier demonstration in the city of Tianjin and the dismissal of the editor of a local youth magazine that had rebuked the sect’s beliefs.

Negotiations continued late into the evening and Falungong leaders departed with promises of a resolution. Within two hours, most protesters were bussed to the distant Beijing West railway station and given tickets home. On July 22, 1999, Beijing outlawed the sect, accusing it of “spreading fallacies, hoodwinking people, inciting and creating disturbances and jeopardizing social stability.” Officials branded Li a charlatan, banned his group’s publications and launched a sweeping crackdown against its members. Then U.S. President Bill Clinton described the offensive as a “troubling example” of the government’s action against those “who test the limits of freedom.”

Performing qigong is supposed to make the wheel turn, enabling practitioners to tap in to the energy pervading the universe. Further, Falungong is unique among qigong disciplines because it is portrayed as a holistic way of living rather than just an aid to good health. Li’s book, Zhuan Falun (“Turning the Dharma Wheel”), the sect’s bible, deals with such moral philosophical concepts as zhen (truth), shan (goodness) and ren (forbearance).

His disciples see him as a “living Buddha.” He also has an astonishing capacity to spread his message. The Falungong has been known to mobilize followers through the Internet and is adept at using videos and publishing material as propaganda tools. Prior to the crackdown on the sect, Li’s books could be found in most bookstores across China, even in state-run outlets such as Xinhua. His works are distributed worldwide in seven languages and taught in China by “cultivation groups” in nine-day classes free of charge. Before the purge, there were as many as 28,000 such groups in the mainland.

Falungong’s membership are often retired people and other marginalized folk who turn to Li’s teachings to fill a spiritual void in their lives. Quite a few are party members. Despite such a following, Li describes himself as “just a very ordinary man.” But that’s clearly not what he set out to be. According to an official probe, Li changed his date of birth from July 7 to May 13, which happens to be the day on which the Buddha was born.