Duterte’s ‘Domino Effect’?

Whether you call Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s badmouthing of the Obama Administration and US Congressional politicians blustering or bluff, there is no doubt that his ‘pivot’ to China and demands for the eventual withdrawal of American troops from Philippine soil has caused considerable anxiety and consternation in Washington. One analyst writing in the National Interest called it the “Duterte Effect” as he questioned whether the loose cannon president is triggering a ‘Domino Effect’ among ASEAN countries in terms of recalibrations of policy toward China and the South China Sea.

Last week, angered by the US State Department’s halt of a planned sale of 26,000 rifles to Philippine police forces, Duterte lashed out at the “fools” and “monkeys” behind the decision. Last week also saw a state visit to Beijing by Malaysian Premier Najib Razak during which he concluded a whopping US$34.25 billion set of 14 agreements which, much to the displeasure of the US, included the purchase of four Chinese-made ships, two of which will be built in China and the other two in Malaysia. Mr Najib also lauded the China-backed Asian Infrastructure Development Bank as a turning point “of peaceful dialogue, not foreign intervention, in sovereign states”. His trip followed closely on the heels of Duterte’s state visit mid last month when he declared a “separation” from the US.

In an editorial in the China Daily, Najib admonished former colonial powers for ill-treating smaller countries, Malaysia having been a colony of Britain and Philippines of Spain and the US for some 50 years before the end of WWII. “It is not for them to lecture countries they once exploited on how to conduct their own internal affairs today”. In spite of being a disputant with China over islands in the South China Sea (which Najib wrote should be settled through bilateral negotiations), Malaysia is keen to strengthen ties with China in the wake of lawsuits filed by the US Justice Department accusing Najib of complicity in the misappropriation of US$3.5 billion from IMDB. Over the summer, Najib dismissed the lawsuits as US interference in the country’s affairs.

So, are we witnessing a ‘domino effect’ involving two key ASEAN countries that could substantially influence the behavior of other smaller Southeast Asian states or is it as one pro-US scholar described as “sensationalism” and “exaggeration” on the part of the Western and other press?

As it stands, within ASEAN, Cambodia (Kampuchea) remains China’s staunchest ally and since the 2014 military coup, Thailand has steadily tilted in favour of Beijing. And while post-election Myanmar is diversifying relations with the West and Japan, Aung San Suu Kyi’s historic 5-day visit to China in summer 2015 resulted in the signing of a big batch of agreements and infrastructure deals. Meanwhile, Laos and Vietnam, while maintaining traditional ties with China, are hedging their bets a little by welcoming all comers, including the docking of both US and Chinese frigates at Vietnam’s Cam Ranh Bay which proved so crucial during the Vietnam War. Finally, although Indonesia’s policies toward China and the US are still a work in progress, Americans can still depend on its all-weather lap dog Singapore for unflinching support. But, even that relationship isn’t as solid as it used to be.

A Chinese foreign policy blogger cited three reasons for Malaysia’s chumming up with China on top of Malaysian annoyance at American-style interference in its domestic affairs: First, China is already investing US$7.3 billion in a major port in the Strait of Malacca with a high-speed rail link-up from China to Thailand and through Malaysia to Singapore coming down the pipeline. Second, on the disappearance of Malaysian Airlines flight MH370, although China exerted strong pressure on Malaysian authorities, it also afforded the country significant leeway in the handling of the search and its aftermath. Finally, Malaysia is keen on playing a central role along the Maritime Silk Road through Southeast Asia and secure a big chunk of infrastructure projects that China proposes to build in the region.

The Japanese government and media are particularly inscensed over the domino effect of Duterte’s stoking of anti-US rhetoric and steering away from the US, Ma Yao, a guest scholar at the International Relations and Public Affairs School at the Shanghai Foreign Languages Institute opined to the Chinese media. First, in a matter of months Duterte has managed to muck up US-Japan’s grand strategy to contain China through a diamond-shaped axis that has been years-in-the-making. Second, a democratically elected Duterte chose to huddle with authoritarian China and negotiate bilaterally on South China Sea claimant issues instead of coordinating policy with the US and Japan and spite of the Philippines’ shared political system and ideology. Third, the Japanese were completely taken aback by Duterte’s behavior who in their view should have consulted with Japan before going to China. That Duterte chose to go to China first was a harder slap in Japan’s face.

At the same time, scholar Ma recognizes that Japan’s fears of dominos vis a vis the South China Sea disputes may be overblown as the US will continue to exert pressure on its allies within ASEAN to stay the course and refrain from negotiating directly with the Chinese. Moreover, despite the Duterte setback, the Americans hold hopes for Vietnam to play a bigger role since, for one thing, it has a much more robust naval force. Finally, few Southeast Asian politicians share Duterte’s style of no=holds-barred cannon blasting and few of them enjoy the strength of domestic political support that the Philippine President currently enjoys. In this respect, the US and the West are criticizing Duterte on the very issue that garners for him such high loyalty. – his war on drugs and taking the fight to drug-traffickers. This is where, among other things, China’s policy of non-intervention has Duterte enamoured.

China Launches Heavy-Lift Long March 5 Rocket

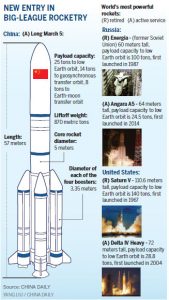

China launched its first heavy-lift Long March 5 carrier rocket late last Thursday, marking a new milestone in the country’s space industry.

As China’s first-generation heavy-lift rocket, the Long March 5 has a liftoff weight of 870 metric tons, and a maximum payload capacity of 25 tons to low Earth orbit and 14 tons to geosynchronous transfer orbit.

The 57-meter-tall rocket, the tallest in China’s carrier rocket family, thundered away with a blinding white flash from the Wenchang Space Launch Center in the island province of Hainan at 8:43 pm. It ferried the Shijian 17 scientific experiment satellite and a Yuanzheng 2 upper stage, which is capable of putting multiple payloads into different orbits during a single mission.

As the nation’s strongest and most technologically advanced launch vehicle, Long March 5 will enable China to put its future manned station into space and send unmanned probes to Mars, according to the State Administration of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense, which oversees the rocket’s development.

China will start launching parts of its permanent manned space station starting in 2018 and put the station into service around 2022. The nation also will send an unmanned probe to Mars to orbit and land around 2020, said space officials.

The Long March 5 rocket has two core stages and four boosters. It uses liquid oxygen/kerosene and liquid oxygen/liquid hydrogen as propellants, making the rocket friendlier to the environment than previous Long March types, according to the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology in Beijing.

Beyond Long March 5, the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology has begun to develop a super-heavy rocket that will have a takeoff weight of 3,000 tons and can lift a 100-ton payload into low Earth orbit.

If the research and development proceed well, the super-heavy rocket will carry out its first flight around 2030, and then it will enable China to land astronauts on the moon and to send and retrieve Mars probes, researchers at the academy said.

– China Daily

Japanese Hold Pervasively Negative Views of China: PRC

Not since the heydays of the late 1970s to early 2000s have the Japanese looked approvingly toward their Chinese neighbours. Dislike for the Chinese have intensified roughly in tandem with Japan’s lost two and a half economic decades and China’s exorable rise. The situation has exacerbated by the rightward turn in Japanese politics, strongly stoked by Shinzo Abe’s government, tainted food imports from China, persistent historical irritants linked to Japan’s reluctance to be fully contrite on documented atrocities committed during WWII, and the vexing dispute over the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands after the shenanigans of ultra-right politician Ishihara Shintaro and their subsequent purchase by the Japanese government

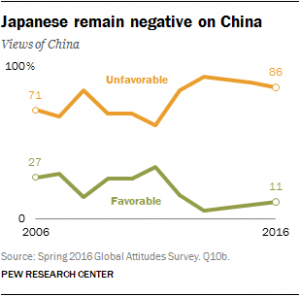

Overwhelming dislike of the Chinese (and vice versa) was once again clearly on display in the latest Pew Research Center (PRC) survey of 1,000 Japanese adults, old and young, conducted late last spring, before the roller-coaster ride over the South China Sea since the summer – the fallout of the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s decision against China’s claims and Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s about-face in navigating his country’s relations with China. Only 11% of respondents held a favourable view of China compared with a startling 86% who held contempt for China and Chinese, including 42% who expressed very unfavorable sentiments. Back in 2002, in a similar PRC survey, 55% of Japanese had a positive view of China.

By comparison, Japan’s views of South Korea are somewhat better with 27% voicing favourable sentiments, though down significantly from the high of 56% a decade ago. Overall, over 2/3 (68%) of Japanese hold an unfavourable view of the Koreans that include one in four who held very negative views. This is hardly surprising given Japan’s lack of atonement on past abuses and atrocities perpetrated on the Korean Peninsula; namely, the use of tens of thousands of comfort women for army brothels during WWII and the legion of forced Korean (and Chinese) labourers for Japan’s wartime industries, and on top of that, territorial disputes. The only major Asian country that the Japanese have positivity in their hearts for is India. No doubt, this stems from the fact that Buddhism emerged from India, the Indian justice’s dissenting judgement in favour of accused war criminals at the Tokyo Trials, and that the country poses no threat to Japan, either economically, being a poor country, or militarily, given India’s fears of China.

The PRC report summarizing the survey attributed the troubling results to being “a manifestation of Japanese fears of a military confrontation with China”. It cites the finding that eight in ten Japanese fear territorial disputes between the two countries could lead to military conflict. However, what’s often been missed in the Western and Japanese press and polling institutions as well is feelings of frustration due to perceptions of dramatic comparative economic decline in the face of the Chinese juggernaut on the part of many Japanese, particularly the young who no longer enjoy lifetime employment working for Japan’s largest conglomerates.

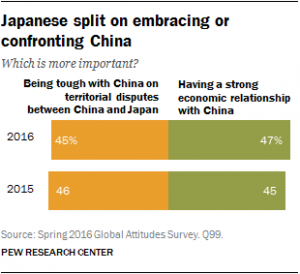

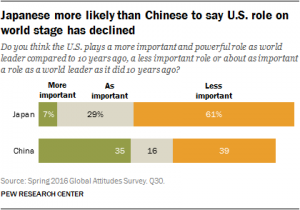

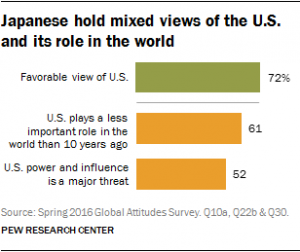

With unfavourable views at all-time highs, the Japanese are nonetheless split on how to best deal with their superpower next door. 47% answered maintaining a strong economic relationship with China is the best policy whereas 45% believed a tougher stance on territorial disputes is better. In stark contrast, 72% of Japanese hold special feelings for the US that has been fairly consistent going back a decade. Their positive take on the US, however, does not translate into an optimistic view of their political master’s trajectory on the world stage. Over 60% (61%) responded that the US is now less powerful and important as a world leader than a decade ago. By comparison, only 39% of Chinese people (in another survey) felt the US is less important than previously.

`What’s more interesting and perhaps paradoxical is that despite their positive outlook on Japan’s most important political and military ally, roughly 1/2 of those polled perceived the power and influence of the US constituted a major threat the country. Ironically, almost 2/3 of young Japanese aged 18 to 34 (63%) were more inclined to hold this view than those 50 years or older (47%). Additionally, a large segment of the population (61%) sees America in decline, a harsher judgement than for China. In the same breath, 61% said the US remains the strongest nation in the world economically with China coming in a distant second with 24%. Only 6% of Japanese saw their country as a world economic leader.

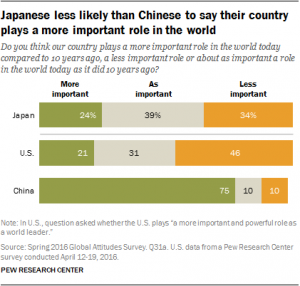

In line with this pessimistic view of Japan’s economic place in the world is public perceptions of Japan’s role in the world community. Only 24% believe Japan plays a more important role in world affairs than 10 years ago while 39% said Japan has held its position and just over a third said their country plays a less important role. In comparison, 21% of Americans and 3/4 of Chinese respondents felt their countries have become more important. But, despite their diminishing view of their country’s world footprint, 59% of Japanese feel Japan should help other nations deal with their problems compared with 35% who believed Japan should deal with its own problems first. Currently, Japan commits 0.22% of its GDP to foreign aid compared to 0.17% for the US and 0.71% for the UK.

Finally, despite their more hawkish stance toward China, the Japanese remain cautious about the country’s military adventures overseas with nearly 2/3 (62%) saying Japan should limit its military role in the Asia-Pacific compared to just 29% who said the opposite, albeit up 6 percentage points over last year. Due to its pacifist constitution which Prime Minister Abe wants desperately to overturn, Japan’s military spending is limited to 1% of GDP. Of those surveyed, only 29% wanted to raise defense spending, and about 1/2 (52%) wished to keep military expenditures about the same level while 14% preferred a decrease. Japan’s military spending compares to nearly 4% by the US, over 4.5% by Russia, and around 2% for China.