China and Japan Agreed to Shelve Diaoyu Islands Dispute: ’82 Suzuki-Thatcher Files

This is yet another revelation about the decision to leave aside differences over the Diaoyu Islands that then Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei’s agreed on as a condition to normalize relations in 1972. Soon after, however, the Japanese Foreign Ministry managed to expunge this seemingly insignificant yet vitally important fact from the official record and has since denied it ever existed. (Senkaku is the Japanese name for the islands)

This is yet another revelation about the decision to leave aside differences over the Diaoyu Islands that then Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei’s agreed on as a condition to normalize relations in 1972. Soon after, however, the Japanese Foreign Ministry managed to expunge this seemingly insignificant yet vitally important fact from the official record and has since denied it ever existed. (Senkaku is the Japanese name for the islands)

The Japanese Foreign Ministry bureaucracy is well known for being obstinate over sovereignty issues despite the inclinations and wishes of elected politicians like Tanaka. Near the end, the article says Japan incorporated the islands through “lawful means” in 1895 after it ascertained there was no control over them. What it fails to mention is the Japanese annexation occurred at the tail end of China’s defeat in the first Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 which the Chinese determined as illegal.

At the start of the 21st Century, the tail that wags the Japanese dog, ultra-nationalist politician Ishihara Shintaro campaigned to buy the islands from its private owners, which effectively broke the status quo and infuriated the Chinese. Then, the Japanese government got into the fray (claiming its hand was forced by Ishihara) by nationalizing the islands which was the last straw for China. The result is the ongoing tension between the two countries.

Japan just couldn’t leave it alone!

The Suzuki-Thatcher conversation is just a small vignette of the goings-on at the Foreign Office from a virtual mountain of documents released this month after 30 years of secrecy maintained at the British National Archives. (See yesterday’s post on the Thatcher government’s attitude toward Hong Kong and mainland China following agreement with Deng Xiaoping on the handover. The British are a cynical bunch!)

———-

Japan and China agreed to maintain the status quo on the Senkaku Islands and avoid any discussion over their respective sovereignty claims, the late Prime Minister Zenko Suzuki was quoted as saying in a 1982 conversation with his then British counterpart, Margaret Thatcher, according to British government files released Tuesday.

The disclosure was made in a record of a private conversation that took place Sept. 20 of that year between then Prime Minister Suzuki and Thatcher. According to the record, Suzuki offered advice to Thatcher on how she should handle the Chinese in negotiations over Hong Kong, then a British territory. The document, prepared by Thatcher’s private secretary, notes, “His (Suzuki’s) advice to the prime minister was to deal directly with (Chinese leader) Deng Xiaoping on the matter, with as few other people present as possible.

“This advice was based on his experience of dealing with the disputed territory of the Senkaku Islands on which, when dealing directly with Deng, he had easily reached agreement that the two governments should co-operate on the basis of their major common interest and leave aside the differences of detail: in consequence it had been agreed that, without raising the matter concretely, the status quo should be maintained, so that the issue was effectively shelved.

“The prime minister welcomed Mr. Suzuki’s advice on the method to deal with Deng, but commented that in the case of Hong Kong it would not be sufficient to shelve the issue if the confidence of investors in Hong Kong was to be maintained.” Also attending the meeting with Thatcher was Yoshio Sakurauchi, at that time foreign minister, and Kiichi Miyazawa, then chief Cabinet secretary and later a prime minister.

In May 1979, as a Lower House politician, Suzuki met Deng in China. This is thought to be the meeting referred to in his discussions with Thatcher. The website of the Foreign Ministry in Tokyo states, “Japan has consistently maintained that there has never been any agreement with China to ‘shelve’ issues regarding the Senkaku Islands. This is made clear by published diplomatic records. “The assertion that such an agreement exists directly contradicts China’s own actions to change the status quo through force or coercion.”

In an effort to bolster its sovereignty claims, Tokyo continues to maintain that there is no territorial dispute over the Senkakus. However, over the years there have been several reports suggesting that both Japan and China have been keen to put the issue on ice and instead focus on building diplomatic and trade ties.

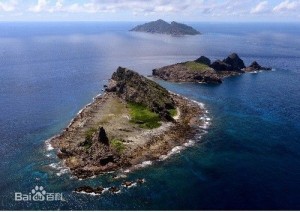

The Senkakus are a small group of uninhabited islets in the East China Sea. In January 1895, Tokyo incorporated the islands into Japanese territory by lawful means after, according to the Foreign Ministry, “having carefully ascertained that there had been no trace of control over the Senkaku Islands by another state prior to that period.”

– Kyodo News Service

Britain Keen on China Trade Not HK Democracy: Foreign Office Documents

30 years after the Sino-British negotiations over the Hong Kong handover, declassified files from the British Foreign Office reveal Thatcher and her government were more concerned about increasing trade with mainland China than any considerations for the rights of Hong Kongers.

Learn some history, ill-educated ‘Occupy Centralers’!

———-

Britain was looking for stronger economic ties with China even before the agreement which would eventually hand it Hong Kong was signed in 1984, secret documents released Tuesday showed.

Ahead of late prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s trip to Beijing in December that year to sign the deal, officials discussed how she should make the case for British business with China.

The files also revealed how China’s then leader Deng Xiaoping reassured Thatcher that his country would keep its side of the agreement, based on the concept of “one country, two systems”, adding that China “always honoured its commitments”.

The documents were released by the National Archives in London under the 30-year rule, which allows previously secret government files to be made public after three decades.

Around six weeks before her trip, the British embassy in Beijing wrote to the Foreign Office urging that Thatcher should “press for greater export and investment opportunities for British industry under the signboard of greater participation in China’s modernisation.”

It added: “It will be important however to handle this in public in such a way that Hong Kong opinion does not see our moves to develop trade as exploitation of the Hong Kong agreement.”

In a nod to this concern, officials decided that Thatcher should not travel with a party of British businessmen to avoid suggestions “that we were now getting our prize for having sold out Hong Kong to the Chinese,” Peter Ricketts, a senior Foreign Office civil servant, wrote to Thatcher advisor Charles Powell on November 16, 1984.

During the trip, business deals including around the development of a nuclear power station in Guangdong were discussed, the files reveal.

Thatcher was also assured by Deng, seen as the architect of China’s economic reforms, over his country’s intentions in Hong Kong.

“Some people harboured doubts about whether China would honour the agreement. Deng said he wished to inform the prime minister and the whole world that China always honoured its commitments,” a British embassy note of the meeting said.

–AFP

China Invests in Greater Mekong

This CNBC article fails to see the forest for the trees. It notes China doesn’t mind low-wage assembly jobs going to countries of the greater Mekong River region.

It’s not just multinational companies that are going there in search of low-wage labour, Chinese companies themselves are financing a lot of the projects in the area that will help prop up labour-intensive manufacturing for which Laos, Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia, and the poorer parts of Thailand can supply plenty of low-wage workers. China is rapidly climbing up the technological ladder and accumulating vast amounts of hard currency with which to invest all over the world. At home, it wants more high-tech jobs, not a continuation of low-wage low-tech assembly.

It is a natural process of Chinese companies going abroad for opportunities (in fact, it’s part and parcel of China’s “going out” policy) and the Chinese government is paving the way with the building of much-needed infrastructure, including the much-touted high-speed rail connection, throughout the region. Why do you think China created the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and President Xi conceived of the Silk Road Fund, not to mention the $11.5 billion the country has already committed for the area. What’s good for the region is good for China and China is helping it to industrialize.

———-