40% of Britons Want to Walk the Great Wall: Survey

Did not realize Britons were so infatuated with the Great Wall.

Here’re their top ten dream destinations:

1.Walking along the Great Wall of China – 40%

2. Hiking into the Grand Canyon – 31%

3. Trekking the Inca trail – 25%

4. Walking the Nile – 21%

5. Diving with great white sharks – 17%

6. Hiking the great Himalaya trail, Nepal – 17%

7. Skydiving over the Great Barrier Reef – 16%

8. Climbing the summit of Mount Everest -15%

9. Expedition across the Antarctic – 13%

10. White water rafting down the Coruh River in Turkey -10

A new survey suggests that far from being couch potatoes as we’re often portrayed, the British are really rather an adventurous bunch. At least in theory…

Figures from the CWM FX London Boat Show reveal that 40 per cent of Brits dream of making a pilgrimage to The Great Wall of China, which stretches for an incredible 5,500 miles across north of the country, while just over a third of people claim that visiting the Grand Canyon in Arizona tops their list of dream destinations.

China is Not Colonizing Africa and There Are Many Players: Economist

This Economist piece starts out okay by debunking recent Western AND certain African portrayals of China’s decade-long engagement with Africa as somehow “neo-colonialist”, “neo-imperialist” or China’s “second continent” as Howard French, the former New York Times China correspondent, titled his new book. But, it seems to confuse Chinese state policy toward Africa such as the China-Africa forum and the many state visits bringing investment and aid with the hundreds of thousands of small-time Chinese businessmen who have been going to the continent in search of business opportunities since the early 2000s. Many intend to stay over the long haul and have made Africa their new home.

The piece is right about the many international players that are now there (in part because of China’s dual challenge of state policy and investment and small business inroads) and China’s explicit rejection of a colonial agenda. China has no troops on the ground aside from UN peacekeepers and it hasn’t any colonial-style administrations in the many countries it deals with. And it doesn’t treat the local people like children needing their governance.

Unlike hypocritical Western countries, China deals with all African countries that want to strengthen ties so China builds railroads in Nigeria, Tanzania, Zambia and Kenya; searches for oil and builds refineries and pipelines in the two Sudans and Angola, and provides over $122 million dollars in medical and financial aid as well as dispatching hundreds of medical personnel to Ebola-stricken countries in West Africa. In short, neither the Chinese state nor its businessmen harbor any dreams of colonial conquest and overlordship in Africa.

However, the Chinese government and state corporations do want resources in exchange for investment and infrastructure building. They also want to help create vibrant markets in Africa. Enlightened self interest works for both sides. If their presence is no longer welcomed, and that won’t come to pass, they can easily find willing partners on other continents such as in Latin America, the Arab world, Eastern Europe, and even parts of North America, notably Mexico. The Chinese government is smart enough to develop a multi-pronged strategy that assures it does not have all its eggs in any one basket. Even if problems do come to a boil, will the West and other countries such as India pick up the slack? Don’t hold your breath.

And what about the legions of small entrepreneurs that opened businesses and factories, set up shops, tilled fields, or otherwise engaged in trade with the continent? It’s about making a living and should circumstance allow, even get rich. If the going gets too tough businesswise or there is too much political backlash, they’ll simply pack up and head for greener pastures and there are many to go to. Should that comes to pass, and it won’t, it will be a loss for Africa, indeed.

———-

China has become by far Africa’s biggest trading partner, exchanging about $160 billion-worth of goods a year; more than 1m Chinese, most of them labourers and traders, have moved to the continent in the past decade. The mutual adoration between governments continues, with ever more African roads and mines built by Chinese firms. But the talk of Africa becoming Chinese—or “China’s second continent”, as the title of one American book puts it—is overdone.

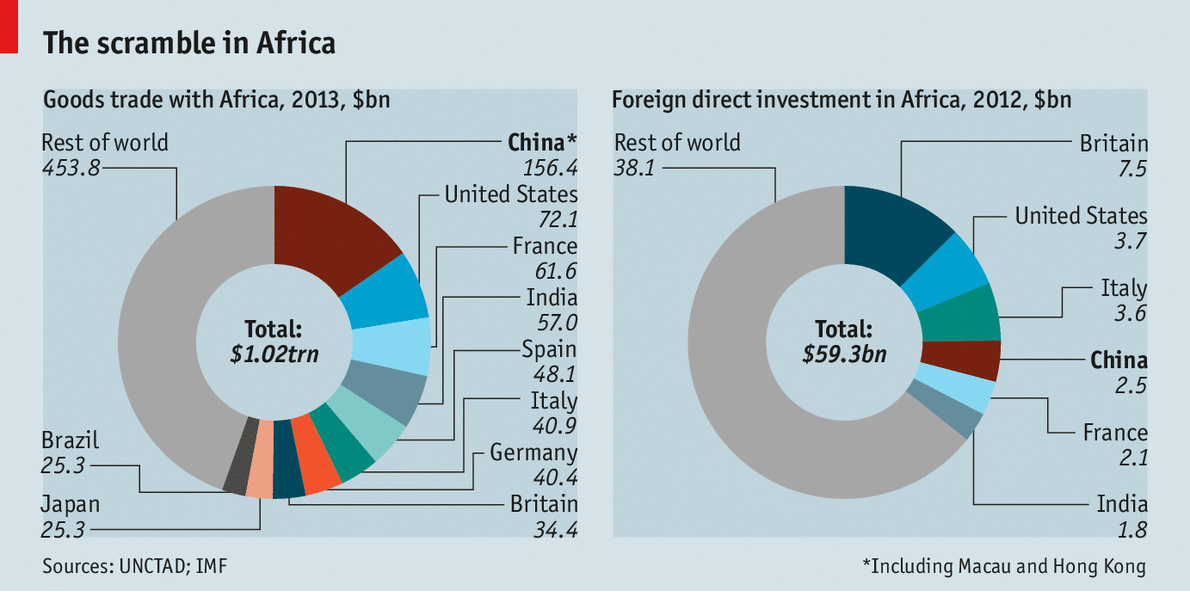

The African boom, which China helped to stoke in recent years, is attracting many other investors. The non-Western ones compete especially fiercely. African trade with India is projected to reach $100 billion this year. It is growing at a faster rate than Chinese trade, and is likely to overtake trade with America. Brazil and Turkey are superseding many European countries. In terms of investment in Africa, though, China lags behind Britain, America and Italy (see charts).

If Chinese businessmen seem unfazed by the contest it is in part because they themselves are looking beyond the continent. “This is a good place for business but there are many others around the world,” says He Lingguo, a sunburnt Chinese construction manager in Kenya who hopes to move to Venezuela.

A decade ago Africa seemed an uncontested space and a training ground for foreign investment as China’s economy took off. But these days China’s ambitions are bigger than winning business, or seeking access to commodities, on the world’s poorest continent. The days when Chinese leaders make long state visits to countries like Tanzania are numbered. Instead, China’s president, Xi Jinping, has promised to invest $250 billion in Latin America over the coming decade.

The growth in Chinese demand for commodities is slowing and prices of many raw materials are falling. That said, China’s hunger for agricultural goods, and perhaps for farm land, may grow as China’s population expands and the middle class becomes richer.

For the article in its entirety see: http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21639554-china-has-become-big-africa-now-backlash-one-among-many

How to Make a Film About Tibetans That Has appeal in China

“Nowhere to Call Home” is the kind of documentary about Tibetan people in China made by foreigners, in this case an American and former NPR journalist, that has intrigued audiences. The film does not engage in self-righteous rhetoric or polemical attacks against China’s “human rights” record. It is rather a fair and personal portrayal of ordinary Tibetans and their trials and tribulations trying to eek out a living in the nation’s capital.

Tibetans face discrimination in Chinese cities, in part because of traumatic events such as self emulations that have occurred over the past few years which the Dalai Lama and his supporters fail to condemn. Only by seeing Tibetans as ordinary human beings with the same problems, albeit more acute, as people among the Han majority have will more Chinese be encouraged to see the film and be empathetic to their plight. And that’s the main purpose of the film.

———-

An American filmmaker has made a documentary on Tibet. Those two elements alone might seem grounds for China’s Communist Party to ban it, but instead the film — Nowhere to Call Home — quietly has been making the rounds in China and winning praise from local audiences.

The reason? The film is an even-handed, deeply personal story that steers clear of politics. Journalist Jocelyn Ford spent years documenting the life of Zanta, a Tibetan migrant who fled her poor, mountain village to build a life for herself and her son in Beijing.

The film, which is simply shot, depicts the abuse Zanta faces in her Tibetan village because she’s a woman and the discrimination she faces in the Chinese capital because she’s Tibetan.

Part of the movie’s appeal is that it demystifies Tibet, which has long held a special place in the Western imagination. In the 1930s novel, Lost Horizon, a British diplomat crash lands in Tibet’s snow-covered mountains and discovers peaceful Buddhists who never age.

“Shangri-La. It was a strange and incredible sight,” says the diplomat, played by actor Ronald Colman, in a 1941 radio play based on the novel. “A group of colored pavilions clinging to the mountainside, like flower petals impaled upon a crag. It was superb and exquisite.”

“We have an expression,” says Zanta, referring to her community. “‘Women aren’t worth a penny.’ Our men are ferocious. If a woman misspeaks, they belt her.”

Zanta, a widow, is battling her father-in-law for custody of her son. The old man, who lives in a largely pre-industrial village, sees no need for the boy, Yang Qing, to attend school. He holds onto Zanta’s and her son’s government-issued ID cards as a way to control them.

Despondent, Zanta moves to Beijing with the boy to seek a better life but has trouble finding long-term lodging. Landlords, who often see Tibetans as oafish and uncivilized, discriminate against her. In one scene, Zanta complains to police after a landlord reneges on renting her an apartment.

“This is an insult to all Tibetans. I’ve lost face,” says Zanta.

“We are all Chinese,” responds a police officer, who is Han Chinese, the country’s dominant ethnic group.

“Chinese bully Tibetans,” Zanta replies bitterly.

Ford, a former China correspondent for public radio’s “Marketplace,” met Zanta while she was selling jewelry on the streets of Beijing in 2005. They exchanged phone numbers. Two years later, Zanta called out of the blue.

Short of money and struggling to raise Yang Qing, she asked if she could give him to the journalist. Instead, Ford began helping finance the boy’s education and documenting Zanta’s life.

Ford is open about crossing the traditional line that separates journalist and subject and even notes when her presence influences the outcome of scenes. By being transparent about her friendship and support of Zanta, Ford says she leaves it to the audience to decide whether her involvement is appropriate.

“When I started making the film, I didn’t think I had a hope in high heaven of showing it in China,” said Ford, following a screening in Shanghai this week. Ford says Chinese audiences seem able to accept the film because it’s a personal journey — not a polemic.

The story can be listened at: