China’s Slow but Assured Economic Rebalancing

The rebalancing of China’s economy is a prolonged and sometimes tortuous process that is best described as “two steps forward, one step back”. In recent years, China’s cheap credit fueled ‘zombie’ state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have been amassing debt on a gargantuan scale pressing the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to issue a warning that the situation is “unsustainable” By some estimates, China’s corporate debt stands at US$18 trillion, equivalent to about 169% of GDP which, although average for a developing economy, is still extremely high by any measure.

Markus Rodlauer, deputy director of the IMF’s Asia-and Pacific Department, told the Telegraph newspaper in early October that “the level of financial and corporate debt and the complexity of the financial system and rapid growth in shadow banking is on an unsustainable path…The longer it lasts…the more serious the disturbance and the disruption might be…While still manageable in its size given the size of the public assets under public control, the trend is dangerous…”

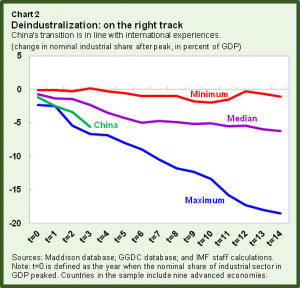

Just as the IMF warning made headlines and despite a 10% dip in China’s exports last month reflecting the fragility of global demand, it was reported that China’s overall share of global exports in 2015 actually climbed to 14.6% from 12.9% a year earlier. This is the highest proportion of world exports ever reported in IMF data going back to 1980. This rise in global export share behooves China naysayers to admit that the manufacturing slice of China’s economy is really declining with the void being filled increasingly by services and consumption as the new drivers of growth.

Longmei Zhang, an economist in the same department at the IMF, writing recently in IMFdirect, used the analogy of a high-powered and fast-sailing ship that nonetheless is listing and drawing some water to describe the current state of structural reform in China. The country has been trying to make the voyage more smoother and balanced and growth more sustainable in four interrelated dimensions’ – external, internal, environmental and distributional. Since the 2008 global financial crisis, she said China has made “mixed-strong’ progress in terms of external balancing, i.e., switching from external to domestic demand and services, but has a somewhat uneven track record in the other dimensions.

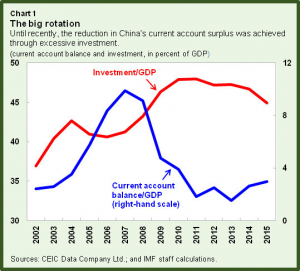

Until 2011, the reduction in the external imbalance was reflected in a growing internal imbalance in terms of the rising levels of investment to GDP ratio due to strong fiscal stimulus. Since 2012, however, some headway has been made away from state-led investment to consumption, both private and state, and from manufacturing to services, with a major bounce in 2015. Consumption now contributes more than 2/3 of GDP growth.

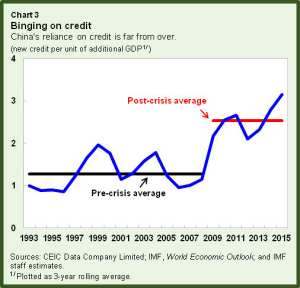

At the same time, however, surging credit usage has become China’s Achilles heel with credit intensity, the amount of new lending provided for each additional unit of output, more than doubling since the global financial meltdown. In addition, while energy intensity of industry has fallen, air pollution remains stubbornly serious as is income inequality even though labour’s share of GDP has steadily grown.

This week, in its marathon bid to rein in high levels of corporate debt, the government announced a set of guidelines that includes encouraging mergers and acquisitions, bankruptcies, debt-to-equity swaps, and debt securitization. The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) emphasized only companies with “good prospects” will be allowed to negotiate swaps with lenders. To date, only a handful of insolvent companies have been given the go-ahead to do debt swaps. In recent years, the Chinese authorities have pledged to introduce more market competitive mechanisms into the lumbering SOE sector and shut down ‘zombie companies’ that are kept alive through easy loans from state banks.

Lian Weiliang, deputy chairman of the NDRC told reporters, “market-oriented debt conversion is by no means a free lunch. The relevant market players will make their own decisions, take their own risks and enjoy the benefits. The government takes no responsibility for bailing out losses.”

The government will combine deleveraging with over-capacity reductions and provide preferential tax relief for firms to cut debt levels. As well, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), China’s central bank, will adopt favourable monetary policies as it pushes banks to transfer bad loans to asset management companies and encourage securitization of bad assets. As this policy package was announced, the central government also resolved to improve market access for foreign companies. In the future, with the exception of certain sensitive industries that are strictly off-limits, foreign investment would only require registration as opposed to approval.

In the backdrop of the recent economic rebound, analysts at US investment bank Morgan Stanley revised their forecast of China’s GDP growth this year to 6.7% from 6.4% and 6.4% from 6.2% for 2017. Moreover, Bloomberg’s survey of 58 economists at the end of September also pegged their expectations at 6.6%, reflecting growing optimism among foreign analysts. In this respect, China must maintain +6% growth to the end of the decade if it wishes to double incomes to US$10,000 by that time. By this writer’s calculation, average incomes should reach $11,000 by end 2020 if the economy can maintain 6.5% growth throughout the decade.