China’s Burgeoning Middle Class Spending

Unbeknownst to the average North American reader, China’s transition to a consumption-led economy has been going on for years. This has led to the burgeoning of a middle class that is progressively cosmopolitan and happier to part ways with hard earned cash in contrast to the previous thrifty and savings-obsessed generation.

Defining China’s middle class as urbanites earning US$9,000 to $34,0000 a year, management consultancy McKinsey and Co. recently projected it will account for 76% of the country’s urban population by 2022, a massive expansion from the tiny 4% in 2000. Last year, China’s urban population approached 730 million or a little over 54% of the entire population which is estimated to expand by one percentage point a year through the 2030s. Even if China’s cities stopped growing, the middle class would still equal 550 million people in seven years, almost 3.75 times America’s whole working population.

More important, the middle class in China is becoming richer in comparison to stagnant middle class incomes in the US and other Western countries. In 2012, China’s “mass” middle class earned $9,000 and $16,000 but within a decade from that date, 54% of Chinese urbanites will be considered “upper middle” class, earning $16,000 to $34,000 a year. That might seem miniscule compared to upper middle class incomes in the US, but adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP), it means a major jolt in consumer spending.

In a similar analysis, the Boston Consulting Group projected Chinese consumption to grow 9% a year until at least 2020 and China’s consumer economy as a whole by 55% to $6.5 trillion from $4.2 trillion last year, based on the conservative setting of China’s GDP growth at 5.5% per annum even though this year’s growth is expected to fall within 6.5% to 6.7%. In addition, Chinese household debt-to-GDP ratio is less than half of US households that currently stands at around 40%. Not only does this mean Chinese consumers spend far less on servicing debts but also that they’re able to take on more debt, if they choose to do so. Culturally and traditionally, however, Chinese families possess a deep aversion to bank debt, preferring to purchase cars, homes, children’s education, and other major outlays with cash or money borrowed from relatives.

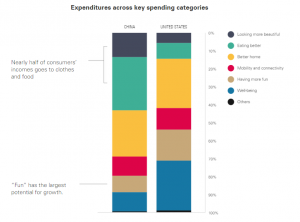

A Goldman Sachs report a year ago described the changing patterns of spending among Chinese consumers. Currently, Chinese families spend on average $7 a day, half on food, compared to $97 a day in the US but as disposable incomes rise, Chinese families will spend more on eating better, dressing nicer, living more comfortably, using more smartphones and cars, having more fun, and spending more on well-being, health, and children’s education. While Chinese consumers prefer to spend more on clothes and food, Goldman Sachs expects them to dig into their pockets for more ‘fun’ – going on vacations at home and abroad, dining out more, and seeking more entertainment and cultural attractions. Currently, Americans spend some 17% of their disposable incomes on having fun whereas Chinese splurge only 9%.

One conspicuously spendthrift group is China’s millennials, those born in the mid-1980s and after. They take trips overseas on a whim, buy stuff more impulsively, and hardly saves at all, much to the chagrin of their parents. A contributor to Forbes magazine writes Chinese millennials are able to keep up their spend-happy ways due to two factors that make their American counterparts envious. First, they are not encumbered by massive student loan debts plus compound interest which American millennials often take decades to pay back, if they haven’t declared bankruptcy already. Chinese millennials enjoy the luxury of their parents paying for their educations which according to Tuition.io averages around $2,200 per year, substantially less than in the US and affordable for most families. In the US, there is a whopping $1.3 trillion in outstanding student loans and more than seven million borrowers in default with tens of millions more struggling to repay.

Second, closely linked to their aversion to household debt coupled with the lack of investment options, Chinese families often plough their funds into acquiring homes with many owing multiple properties that explains to a large extent China’s inability to rein in real estate bubbles across the country. Looking out for their offspring, Chinese parents often hand over an extra apartment that saves millennials immense costs associated with securing a home on their own. By comparison, in the US, millennials, already loaded down with student loans, can hardly afford to rent decent apartments, let alone considering to buy a home. This also explains why millennials in the West travel less and spend far less on the trips they do take than their Chinese counterparts.

By 2020, Chinese millennials will top 300 million (compared to 80 million in the US) who, unlike their parents that are fixated with famous brands and acquiring properties, will form the second generation of Chinese consumers. This group desires to be more spiritually and culturally fulfilled, venturing overseas to expand their horizons and living for the moment. While many will still follow the crowd on group tours, the adventurous minority will want more individualized experiences, preferring to explore sites off the beaten path. And many will continue to indulge in luxuries while others focus on family and children, less burdened by mortgages and car loans like their Western brethren.

Not to be forgotten, a final mainstay of China’s consuming horde is the increasing legions of the elderly. Another recent study by McKinsey & Co. builds on the findings of a previous analysis in 2011 (here I focus on the elderly). The authors state that five years ago, they had grossly underestimated the speed and force of spending by the Chinese elderly. Much of what they had anticipated would happen in 2020 already started happening in 2015. 52% of the 55-65 age group expressed preference for premium products as compared to 32% in 2012 and constituted the group most likely to trade up in their buying habits. They no longer shun famous brands, do not shy away from indulgences, and have grown more accustomed to researching their purchases online.

The Chinese middle class has come into its own and we’re witnessing only the start of China’s ever expansive, changing, and increasingly sophisticated consumption trends that bode well for major surges in imports from abroad.