A Blind Activist and China’s One-Child Policy

Finally, a possible face-saving compromise for the two superpowers may be at hand to resolve the case of Mr Chen Guangcheng, the blind abortion activist from rural Shandong. Mr Chen, aided by US-backed sympathizers, ‘daringly escaped’ from captivity into the US Embassy and then flip-flopped on whether he would stay or seek asylum in the US. Mr Chen managed to singlehandedly hijack Tim Geithner and Hillary Clinton’s meetings with senior Chinese leaders at the all-important 4th Strategic and Economic Dialogue (SED) talks in Beijing that just concluded.

The Chinese government announced that Mr Chen could apply to study in the US and would process his travel documents accordingly as well as making accommodations for his medical condition. The US State Department confirmed that Mr Chen has been offered a fellowship from an American university where he could be joined by his wife and children. Read: asylum granted.

Whew! What a relief! But, on top of dousing the fire of the SED, the diplomatic faux pas once again put China’s ‘draconian’ one-child policy under the international spotlight, drawing the ire of Western commentators, columnists and editors. Lest more people get hot under the collar, we should get some basic facts straight and put the policy in perspective.

Formerly lauded for his work on rights for the disabled, Mr Chen crossed the authorities in Linyi, Shandong, when he started exposing egregious abuses in the city’s enforcement of one-child policies, including forced sterilizations and abortions. Violations by local officials, which occur across China, contravene a 2002 national law banning the use of physical force to enforce compliance. Faced with contempt for the policy, jurisdictions often resort to drastic actions in imposing strict quotas.

The policy is strongly enforced for the Han in urban areas unless both parents are themselves single children, or if their first child has a physical or mental disability. However, in the countryside, a second child is allowed if the first is a girl, a bonus concession in light of the traditional bias toward boys that pervade among the peasantry. However, in the remote countryside, it is not uncommon to find families with 3 or 4 unregistered children. Further, as part of its affirmative action policies for national minorities, non-Han groups are exempted from Han restrictions, allowing them to bear 2 children in the cities and 3-4 in the countryside.

For rule-abiding parents, a monthly stipend is provided along with extra pension benefits, preferential hospital treatment and housing benefits, preferred consideration for government jobs, and even bonus points for their children in taking middle school entrance exams. The authorities monitor young families closely and often use communal pressure, notwithstanding the abuses uncovered by Mr Chen.

For those who violate the law, in many provinces, fines, sometimes several times the annual net family income, are meted out. However, in spite of the heavy penalties, rich Chinese continue to flaunt the policy, such the case of a Guangdong couple that paid almost 1 million RMB to have 8 children through surrogacy, arousing much disgust and condemnation on the Internet.

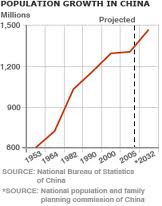

Following the introduction of the one-child policy in 1979, China’s fertility rate has fallen from over 3 births per woman in 1980 to approximately 1.54 in 2011. Based on the latest census, China’s population has reached 1.35 billion and is projected to peak around 2030, leading critics to declare that the policy has exacerbated the rapid aging of society. By contrast, in India which is facing a demographic explosion and whose population is expected to surpass China’s by 2025, the fertility rate remains high at 2.64 births per woman (another study puts the figure as high as at 2.9).

In 2008, the Chinese government estimated that had it not been for the policy, there would be 300 to 400 million more people, putting immense pressures on the food supply, resources, public health, education, pollution, and social services. Other experts add that trends attributed to modernization such as lower rates of infant mortality, wide availability of contraception, and greater participation of women in the workplace have contributed to fertility declines. Moreover, younger women in Shanghai, Beijing and other major urban centers, as they become richer and more educated, are marrying later and opting to have fewer children, just like their counterparts in developed countries.

Many experts contend that the one-child policy has heavily skewed the birth sex ratio on the mainland vastly in favour of males, reaching as high as 117:100 in 2000, substantially higher than the natural baseline ranging from 103 to 107:100. As a result, by 2020, estimates China’s National Population and Family Planning Commission, there could be 30 million more men than women, potentially leading to social instability and heightened foreign bride-seeking. Other parts of East Asia have exhibited similar patterns with South Korea reaching 116:100 in the 1990s although the figure has dropped to normal levels since the mid 2000s.

Should/will China relax its one-child policy, given demographic changes it has helped to engender and abuses caused in its implementation?

There are frequent calls to tinker with the system such as last summer’s appeal in Guangdong to allow a second child for urbanites, following precedents in Shanghai permitting a second child for single-children parents, but Beijing’s family planning authorities have consistently upheld the status quo. China’s surging urbanization, some 15 – 17 million new city-dwellers a year over the next 20 years, will ensure that the policy stays intact in its basic form. Only when palpably negative effects on economic development are felt will central authorities do a fundamental re-think.